Study Day, 26 April 2017

Schulich School of Music, McGill University, Montreal, Quebec, Canada in conjunction with the Musée des beaux-arts de Montréal

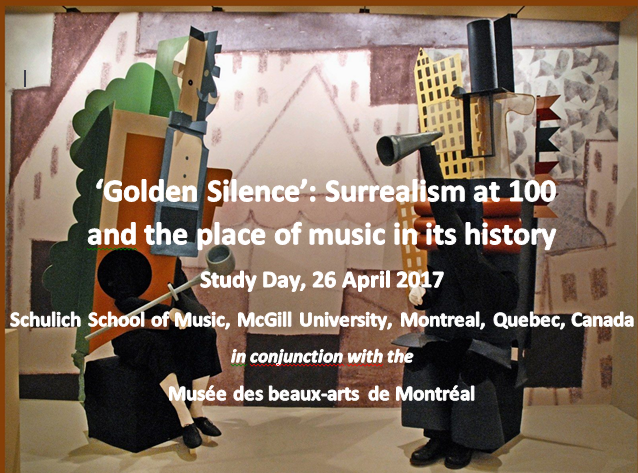

Just a few weeks short of 100 years ago, on May 18 1917, a Parisian audience witnessed the première by the Ballets Russes of a new work, ‘Parade’, to a scenario by Jean Cocteau, with choreography by Léonide Massine, sets and costumes by Pablo Picasso and music by Erik Satie.

Cocteau called ‘Parade’ a ‘ballet réaliste’, but this term should be understood in the context of Picasso’s metamorphic treatment of reality using the techniques of Cubism. In a similar way, according to Cocteau, Satie’s music achieved the trick of enabling one somehow to ‘hear’ simultaneously ‘la parade et le spectacle intérieur’. Using an analogy from the visual realm, he spoke of the ‘tromp-l’oreille’ effect of using ‘real-world’ noises – a typewriter, revolver, sirens, etc. – as part of the score.

For the poet Guillaume Apollinaire, who provided a programme note for the new ballet, the term ‘réaliste’, even if understood in this rather special way, did not adequately describe the novel approach to reality demonstrated in ‘Parade’. Instead, he proposed the work as the prototype for ‘une sorte de sur-réalisme’, one in which he saw the first consummation of ‘cette alliance de la peinture et de la danse, de la plastique et de la mimique qui est la signe de l’avènement d’un art plus complet’.

This study day celebrates the strong association of music with the origins of Surrealism but also examines the relatively slender involvement of the art-from with the movement’s subsequent history. Finally, it poses the question as to whether, as Surrealism enters its second century, its relationship to music might find a deeper and more extensive expression than for the majority of the last 100 years.

Cocteau called ‘Parade’ a ‘ballet réaliste’, but this term should be understood in the context of Picasso’s metamorphic treatment of reality using the techniques of Cubism. In a similar way, according to Cocteau, Satie’s music achieved the trick of enabling one somehow to ‘hear’ simultaneously ‘la parade et le spectacle intérieur’. Using an analogy from the visual realm, he spoke of the ‘tromp-l’oreille’ effect of using ‘real-world’ noises – a typewriter, revolver, sirens, etc. – as part of the score.

For the poet Guillaume Apollinaire, who provided a programme note for the new ballet, the term ‘réaliste’, even if understood in this rather special way, did not adequately describe the novel approach to reality demonstrated in ‘Parade’. Instead, he proposed the work as the prototype for ‘une sorte de sur-réalisme’, one in which he saw the first consummation of ‘cette alliance de la peinture et de la danse, de la plastique et de la mimique qui est la signe de l’avènement d’un art plus complet’.

This study day celebrates the strong association of music with the origins of Surrealism but also examines the relatively slender involvement of the art-from with the movement’s subsequent history. Finally, it poses the question as to whether, as Surrealism enters its second century, its relationship to music might find a deeper and more extensive expression than for the majority of the last 100 years.

For more information about the event please visit the event web-page.